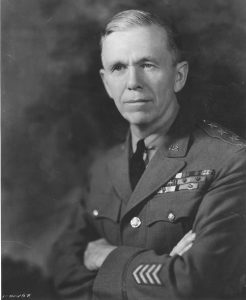

Army Chief of Staff Marshall

Deputy Chief of Staff George C. Marshall assumed the chief’s duties on July 1, 1939. According to army regulations: “The Chief of Staff is the immediate adviser of the Secretary of War on all matters relating to the Military Establishment and is charged by the Secretary of War with the planning, development, and execution of the military program. He will cause the War Department General Staff to prepare the necessary plans for recruiting, mobilizing, organizing, supplying, equipping, and training the Army of the United States for use in the national defense and for demobilization. As the agent, and in the name of the Secretary of War, he issues such orders as will insure that the plans of the War Department are harmoniously executed by all agencies of the Military Establishment, and that the military program is carried out speedily and efficiently. . . . The Chief of Staff, in addition to his duties as such, is, in peace, by direction of the President, the Commanding General of the Field Forces and in that capacity directs the field operations and the general training of the several armies, of the oversea forces, and of GHQ units. He continues to exercise command of the field forces after the outbreak of war until such time as the President shall have specifically designated a commanding general thereof.” (Army Regulation No. 10-15, August 18, 1936 [Washington: GPO, 1936], p. 1.)

With his July 5, 1939, Executive Order, President Roosevelt strengthened the commander in chief’s relationship with the chief of staff. Roosevelt directed that the Joint Board and other service officers should report directly to him on certain issues instead of through their departmental heads. (Mark S. Watson, Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans and Preparations, a volume in the United States Army in World War II [Washington: GPO, 1950], p. 2.)

Marshall outlined a condition of unpreparedness which so shocked Harry Hopkins that he recommended that Deputy Chief of Staff Marshall tell President Roosevelt right away. Marshall refused, but gained the support of Hopkins, who Marshall credited with influencing Roosevelt’s final decision for chief of staff. Pictured are Marshall and Hopkins in 1942.

Marshall insisted on keeping his distance from Roosevelt while maintaining his loyalty to the president. He never visited the president in Hyde Park or Warm Springs, despite Harry Hopkins’s urgings. “I was not on that basis of intimate relationship with the president that a number of others were,” Marshall recalled. “I had to be proved. He had appointed me without any large war experience (except for being with General Pershing in the First World War and for a time chief of operations of an army of almost a million men), and I was pretty young. It was quite a long time before he built up confidence in me to anything like the extent that he apparently had in the last year of the war.” (George C. Marshall Interviews and Reminiscences for Forrest C. Pogue, ed. Larry I. Bland, 3d ed. [Lexington, Va.: George C. Marshall Foundation, 1996], p. 417. This source is hereafter cited as Marshall Interviews.)

Beginning immediately after the April 27, 1939, announcement of Marshall’s appointment, a wave of congratulatory letters and telegrams flooded his desk—so many that the general recruited his stepdaughter Molly Brown to assist the office staff in answering them. Thirty-six friends and colleagues wrote Marshall that they had earlier—in some cases decades earlier—predicted his appointment. Dozens more wrote that they had felt certain that he would someday become chief of staff. To one friend writing belatedly, Marshall replied: “I am very glad that you waited until about fifteen hundred or more letters went through at railroad speed, because I have the leisure this morning to enjoy and thoroughly appreciate that you were good enough to write.” (Marshall to Captain O. D. Wells, July 19, 1939, GCMRL/ G. C. Marshall Papers [Pentagon Office, General]. Nine hundred eighty seven congratulatory messages are preserved in Marshall’s files.

Recommended Citation: The Papers of George Catlett Marshall, ed. Larry I. Bland, Sharon Ritenour Stevens, and Clarence E. Wunderlin, Jr. (Lexington, Va.: The George C. Marshall Foundation, 1981- ). Electronic version based on The Papers of George Catlett Marshall, vol. 2, “We Cannot Delay,” July 1, 1939-December 6, 1941 (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), pp. 3-4.