By: Wayne C. Thompson

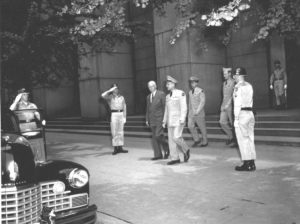

On September 21, 1950, George C. Marshall, who had been happily retired from national service since stepping down as secretary of state in January 1949, became America’s third secretary of defense. The post and department had been created by the National Security Act three years earlier. The young department was the government’s largest and required an exceptional leader, especially since June 25, 1950, when war raged in Korea. The first secretary, James V. Forrestal, was so overwhelmed by the responsibility that he committed suicide. The second, Louis A. Johnson, fueled intra-departmental rivalries and acrimony. He was unable to tame his hatred of Secretary of State Dean Acheson. This cost him the trust of President Harry S Truman.

America faced two principal crises. Truman was convinced that the greatest threat stemmed from Soviet aggressive ambitions in Europe. A strengthened and united Atlantic alliance was needed as a deterrent. America’s top military leaders, including Marshall, were persuaded that the defense of Europe could not be achieved without West German participation. However, many Europeans, especially the French, could not accept a rearmed Germany so soon after World War II. What was needed in the tense negotiations was a trusted leader with intimate knowledge of European concerns who could reassure all parties. That leader was the father of the Marshall Plan himself. Acheson wrote that his presence “in the last year of grave peril to our country…steadied all of our vital actions and decisions.” The Federal Republic joined in May 1955.

The second crisis was in Korea, where North Korean troops had launched a surprise attack on June 25, 1950. American combat troops had been withdrawn a year earlier, and those U.S. soldiers still there were unprepared and poorly equipped with left-over WWII kit. JCS Chief Omar Bradley called it the “wrong war in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Truman counted on Marshall’s guiding hand to avoid a nuclear war and to accustom Americans to the Cold War reality of limited war. Total war had become unthinkable in the nuclear age. He resolutely supported the objective, “Europe first,” and helped make NATO effective. He restored America’s fighting power and confidence without harming the national economy by putting it on a total-war footing.

His prestige was also needed to place limits on a military idol, General Douglas MacArthur, who repeatedly disregarded the president’s directives. Marshall supported, but did not initiate, MacArthur’s dismissal from command on April 11, 1951.

Marshall agreed to serve an additional half of a year until September 12, 1951. He left an enduring legacy to his country and the DOD. He brought order to the infant department. He produced an amical relationship with the state department. Deferring always to the secretary of state on political matters, he strengthened the principle of civilian predominance over the military. He skillfully balanced diplomatic and military concerns. He was a respected arbiter between the distinct armed services and thereby helped to reduce inter-service rivalries.

After one year in office, he concluded that “now appears to be as appropriate a time as any to wind up 50 years of uninterrupted daily service to the government.”

About Wayne C. Thompson

Professor Wayne C. Thompson taught politics at the Virginia Military Institute and Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. He received his doctorate in government from Claremont Graduate University in California and has authored, co-authored or edited ten books. He is currently preparing a book for future publication entitled: A General’s Last Call. George C. Marshall as Secretary of Defense, 1950-1951.

If you like reading our blogs, please support us by becoming a member of the Foundation.