In late 1938, a decoded Japanese message indicated that in February 1939, the current “A” encryption would no longer be used, but would switch to the new “B” encryption.

Japanese diplomatic messages had been decoded and read from the “A” encryption for several years, so the switch was at first worrisome, and then problematic, for Maj. Gen. Joseph Mauborgne, the U.S. Army Chief Signal Officer. None of his team was able to decode the new “B” messages, so he called an old friend he’d first met in World War I, and who was working in the Signals Intelligence Service, codebreaker William Friedman.

Maj. Gen. Joseph Mauborgne

As told by his wife and fellow codebreaker, Elizebeth:

“One day, Mauborgne had called him into his office and said, ‘I want you to drop everything and take charge of this group that is working on the Japanese diplomatic cipher system. They aren’t getting anywhere. You drop everything and take care of it.’”

The Signals Intelligence Service in 1935 Seated: Mrs. Louise Newkirk Nelson; Standing, left to right: Mr. H.F. Bearce (later Lieutenant Colonel), Dr. Solomon Kullback (WWII Colonel), Captain Harrod G Miller, Mr. William F. Friedman, Dr. A. Sinkov (WWII Colonel), Lieutenant L.T. Jones, USCG, and Mr. Frank B. Rowlett. Mr. John B. Hurt was ill when the picture was taken

Elizebeth went on to say that “they didn’t even know when they started working with those cipher messages that it was a machine cipher. They didn’t even know that. There’s all the difference in the world between machine cipher and paper cipher. Machine cipher can go into hundreds and billions of computations. You can start from here and go to the end of the world and never have a repetition.”

William Friedman in his Army Signal Corps uniform in the 1930s

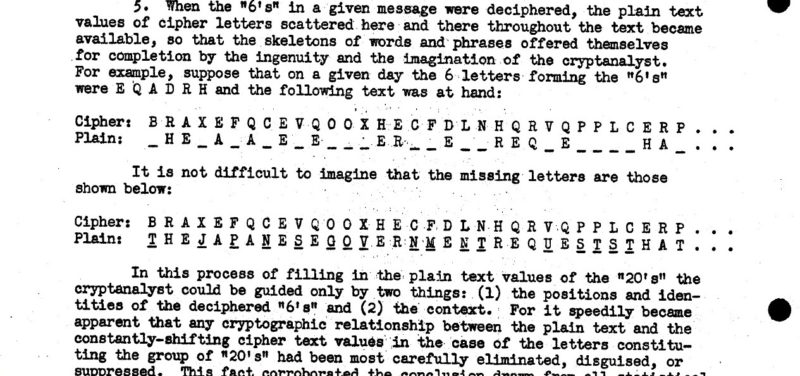

The new code was found to have six letters that appeared more than the other 20. Through a diligent system of daily charting of these six letters, Friedman and his team were able to determine what the “6’s” were by April 1939, and started to be able to decode the messages, using the determined “6’s” as skeletons for the words.

Using the “6’s” as skeletons for words

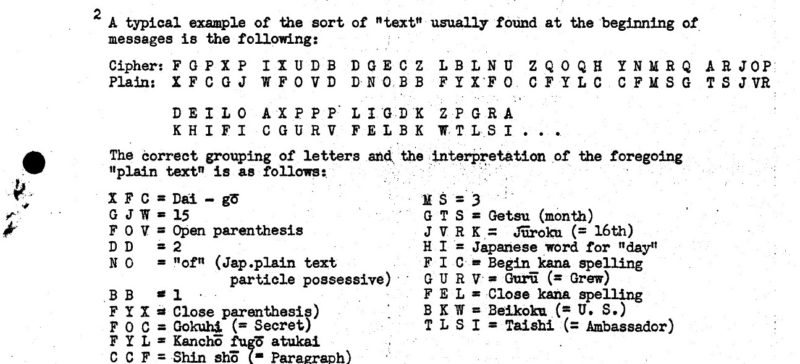

Filling in the words became more difficult in May, as “long series of arbitrary letters and abbreviations standing for numbers, punctuation signs, and frequently used combinations of letters, syllables, words, and sometimes complete phrases” began being used, according to Friedman. For example, “CFC” stood for a period at the end of a sentence; and “BKW” meant the United States. “The difficulties introduced by this … were quite staggering as well as aggravating, for often the ‘text’ even when finally reconstructed appeared more like code or a random assortment of letters than plain text,” commented Friedman.

Figuring out the letter groupings in the plain text

“In running language, the message begins as follows: ‘Number 15 (part 1 of 2 parts) Secret, to be kept within the Department paragraph On March 16th the American Ambassador…’” wrote Friedman.

The decoded text of about 15 messages were “subjected to most intensive and exhaustive cryptanalytic studies,” according to Friedman, but “to the consternation of the cryptanalysts, it was found that not only was there a complete and absolute absence of any causal repetitions within any single message,” but that “when repetitions of three, or occasionally four, cipher letters were found, these never represented the same plain text.” He went on to say, “a statistical calculation gave the astonishing result that the number of repetitions actually present in these cryptograms was less than the number to be expected had the letters comprising them been drawn at random out of a hat!”

Instead of being a problem, this realization actually contributed to solution of this new coding, but it wouldn’t happen easily. Friedman and his team spent exhaustive effort and many, many hours trying to discover the “cyclically repeating keys or sequences.” They realized that their efforts were fruitless in part because they didn’t have many messages yet to work with. They would need several messages using the same indicator text from the same day, or convert messages with the same indicator text from different days to the same text before they could find these cyclic sequences. Out of over a thousand messages, six with the same indicator text were found, and on Sept. 20, 1940, the first repeating sequences were discovered. “There was much excitement at this first glimmer of light upon a subject that had for so many months been shrouded in complete darkness and regarded occasionally with some discouragement” commented Friedman.

The Friedman family about the time William broke “Purple”

After near-round-the-clock work over the next week, two translations of this “B” code were handed in Sept. 27, thus breaking the Japanese Diplomatic “Purple” code. In his report, Friedman noted that “the successful solution … is the culmination of 18 months of intensive study by a group of cryptanalysts and assistants working as a harmonious, well-coordinated and cooperative team. Only by such cooperation and close collaboration of all concerned could the solution possibly have been reached, and the name of no one person can be selected as deserving of the major portion of credit for this achievement.”

Some of the many personnel who worked in the Signal Intelligence Service in Arlington Hall, during World War II. Standing left to right: Mr. Mark Rhoads; Colonel Kullback; Mr. John Hurt; Unknown; Colonel Rowlett; Colonel Sinkov; Colonel M. Grail; Colonel Corderman; William F. Friedman

William Friedman and his team did not rest on their success, though; they used what they’d learned and immediately began to reverse-engineer a machine that could read and decode the incoming messages, which was completed by the end of 1940.

Information for this blog is from an interview given by Elizebeth Smith Friedman to the library staff at the George C. Marshall Foundation in 1974, and from “Preliminary Historical Report on the Solution of the ‘B’ Machine” by William Friedman from October, 1940.

Notes:

Photo of Maj. Gen. Joseph Mauborgne from the National Cryptologic Museum Foundation

All other photos are from the George C. Marshall Foundation William Friedman Collection.

Melissa has been at GCMF since last fall, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @life_melissas.