Why did codebreakers William and Elizebeth Smith Friedman, cryptographers for the departments of the Coast Guard, Navy and Army for many years, and who helped found the National Security Agency, leave their library and papers to the George C. Marshall Foundation?

Their choice began with an evening visit to the Friedman home by NSA personnel June 26, 1959. Items that had previously been declassified were removed from the Friedman’s collections and reclassified, much of the material from World War I. It irritated and mystified Elizabeth and William, who wrote, “Even the smallest nations don’t care a fig about them.”

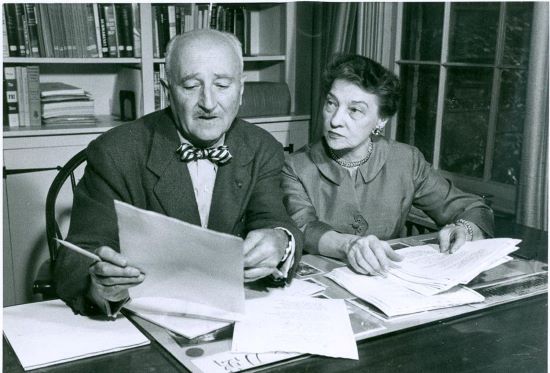

William and Elizebeth on his retirement from the NSA, Oct. 12, 1955.

The Friedmans already had reservations about the government’s classification system. This episode made them certain that if their library and papers were left to the government, everything would be stamped “classified,” put in a vault and never again see the light of day. William and Elizebeth wanted their collections open to researchers and freely available, so they began looking for a permanent home for their material. Several universities pursued their collections, but the Friedmans wanted a small organization to whom their library and papers would be important. They also wanted their donation to have its own room.

While it’s likely that Capt. William Friedman and Col. George Marshall met while both were working in the General Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Forces in France during World War I, their careers took different paths after the war, and it’s not known if they met again later in life. Elizebeth and William admired Marshall for his integrity and dedication, and when they saw in the early 1960s that a foundation building in his name was being built on the campus of his alma mater, the Virginia Military Institute, they began taking the local paper, the Lexington Gazette, to follow its progress.

George C. Marshall Foundation building, c1964.

After they visited the new George C. Marshall Foundation building, they made their choice. The Friedmans began working on an inventory of their books, papers, and photos in preparation to make their donation.

William and Elizebeth in their library.

On October 22, 1969, William wrote in frustration, “What to do about those early writings of mine which are still held in the vaults of the NSA and copies of which I was not permitted to retain? I have practically given up hope of being able, at long last, to get those things released so that they might be integrated with the things included in my gift to the Marshall Library.”

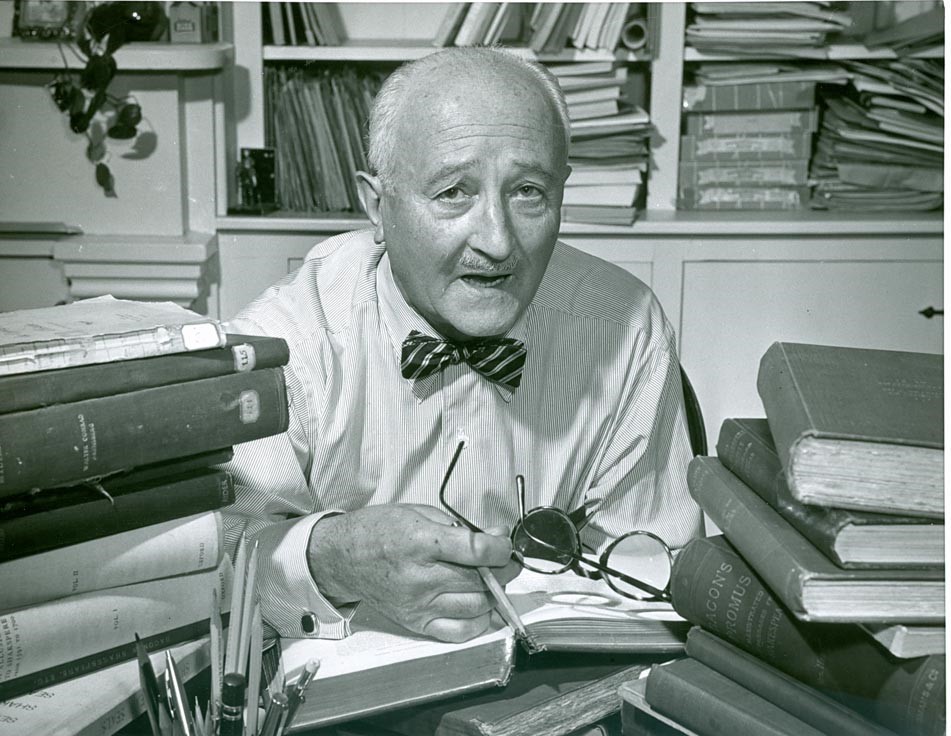

William working in the library of the Friedman’s Capitol Hill home.

Two weeks later, William died of a heart attack. Elizebeth plowed on with the inventory, and in 1971, she supervised the packing of their library, papers, the desk from their Capitol Hill home, and a small safe to which only she had the key, into a truck. She then got in her car and followed the truck to the Marshall Foundation where she supervised the unloading.

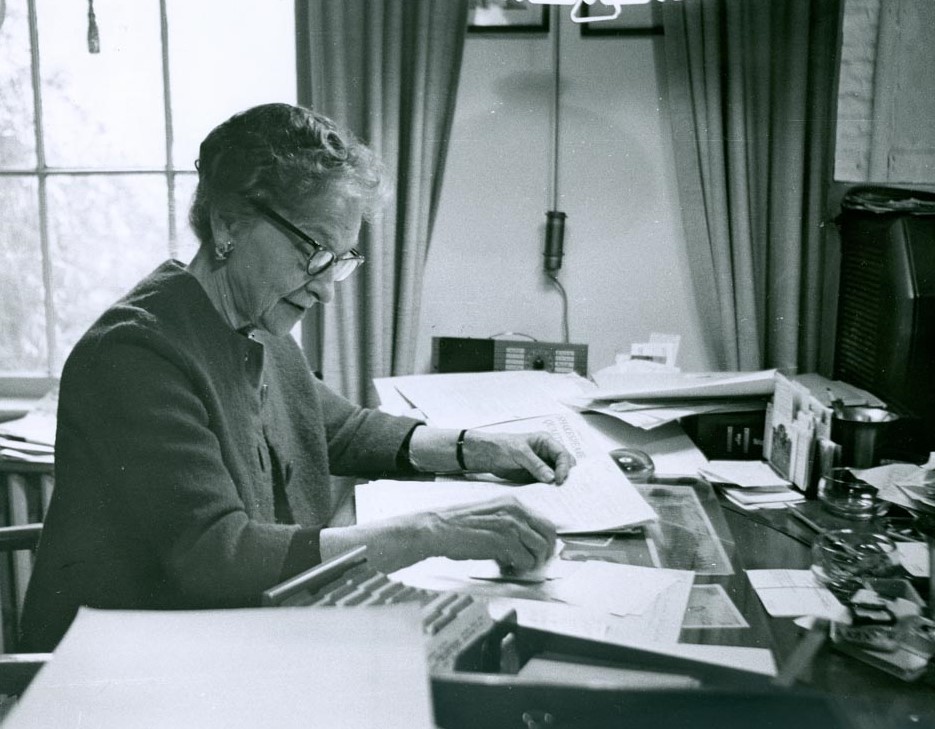

Elizebeth working on the collections inventory.

Elizebeth spent quite a bit of time over the next several years at the Foundation, acquainting the library staff with their new collections and sitting for taped interviews. When the archivist asked if the Friedman’s library could be recataloged into the Library of Congress system, Elizebeth said no. The Friedmans cataloged their books numerically and she wanted it to stay that way. The original numbered labels are still on their books.

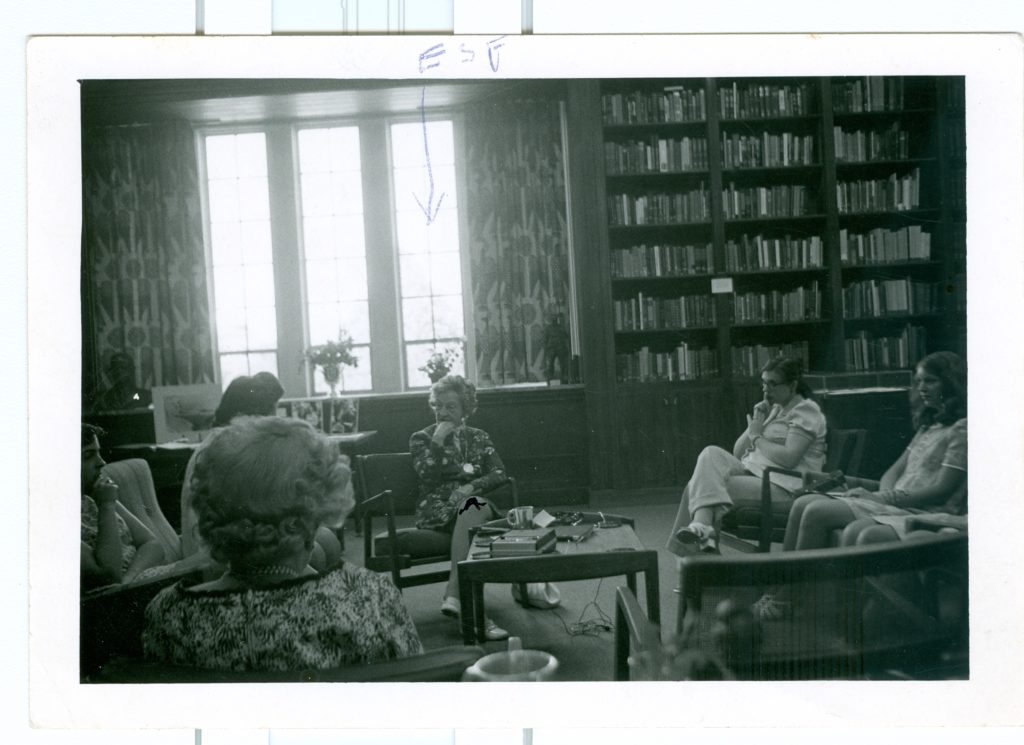

Elizebeth in the Marshall Foundation Library, visiting with library staff.

When Elizebeth died on Halloween 1980, she didn’t realize that the Friedman collections would become some of the most popular at the Marshall Foundation, used not only by researchers, but junior- and senior-high school students who want to know more about the amazing William and Elizebeth Smith Friedman.

Before becoming director of library and archives at the George C. Marshall Foundation, Melissa was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Melissa is known as the happiest librarian in the world! Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.