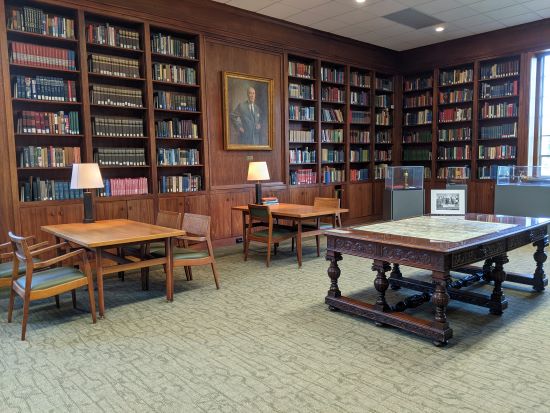

The main library room at the George C. Marshall Foundation is called the “Lovett Reading Room,” and there is a large painting of Robert Lovett on display. This confuses some visitors who may not recognize Lovett, or know the long working relationship George Marshall and Lovett had.

Marshall Foundation Library, Lovett Reading Room

Painting of Robert Lovett

Lovett was a World War I pilot who became a banker after the war. He entered government service in the summer of 1940, as Assistant Secretary of War for Air to Secretary of War Henry Stimson. Although Marshall did not believe that with air power, the United States didn’t need an Army of foot soldiers, “Marshall was not slow in appreciating airpower certainly,” Lovett said to Marshall biographer Dr. Forrest Pogue.

In the same interview, Lovett explains his expertise on air power, in part gained from visiting production plants:

I spent several weeks on the Pacific coast in airplane plants. We were abysmally weak. We had not appreciated the potential striking power of planes. I wrote out a short report–about three pages–on what I saw and thought. Jim Forrestal, a neighbor and a close friend, asked to see the report. He gave copies to Judge Patterson and Colonel Stimson. They asked if I would come down and be assistant secretary of war for air. I went first in November 1940 as special assistant.

While Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold commanded the Army Air Forces during World War II, Lovett worked on the procurement of aircraft. With Marshall and Arnold supporting him, he got factories started on building airplanes before the official contracts were awarded, as Lovett said; “we had talked the aircraft companies into accelerating their programs without much appropriations. They gambled on getting them. We were particularly deficient in big bombers and interceptor fighters.”

Lovett was privy to some of the discussion around the choice of commander for the invasion of Europe. He later said, “Marshall would have loved the command, but Roosevelt recognized that the man who ran things in Washington was bigger than the man who commanded in the field. King went to Roosevelt and said if you take Marshall this will fall apart. Marshall was the great rallying point.” He elaborated on why Marshall was the “great rallying point,” saying, “People had veneration for Marshall. A great modern war requires so many qualities which Marshall had in great measure. Marshall [was] marked by gravity [and] moral distinction; above rivalry.”

When Marshall became Secretary of State, he created the Policy Planning Staff, and different ways of distributing responsibilities to be more efficient. Having seen Lovett in action, Marshall decided he wanted Lovett working with him in the State Department. A few days after being sworn in, Marshall asked Lovett to be Under Secretary of State when Dean Acheson left that spring:

I hope that you can give favorable consideration to my proposition. The President was very enthusiastic over it. But as for me, it would mean a great deal to feel that I could look to a man with your character and ability to take over the job of Under Secretary, and also to put into being the very important phase of the State Department’s interests in connection with communications and air in particular.

When Lovett accepted, Marshall was thrilled, writing

Dear Lovett: I was very much pleased and relieved to receive your letter of February 11 indicating your willingness to accept the appointment as Under Secretary of State.

I cannot tell you what a relief it is to me to feel that I will have your strong support during the difficult days ahead. I contemplated with almost fear the departure of Acheson with no assurance of just who I would have to assist me in his stead. Now that I know you are willing to take on the chore, my whole point of view has changed and my spirits are lightened accordingly.

With warm regards and my earnest personal thanks.

Marshall and Lovett worked many hours together pushing the legislation funding the Economic Recovery Act throughout late 1947 and into 1948. They made numerous appearances testifying in Congress and answering questions. Of these months, Lovett commented, “I worked so closely with him I am entirely biased in his favor. I don’t suppose there has been a relationship as close as that we had. I am endlessly grateful to have had a chance to work with him.”

Marshall and Lovett appearing before Congress regarding the passage of the Economic Recovery Act.

The trusting relationship between Marshall and Lovett grew to the point that Marshall trusted Lovett to communicate with President Truman for him when he was out of the country. While Marshall was in London in December 1947, he wrote that he wanted the President to give “Lovett a full opportunity to present my views on the matter” of the European Recovery Plan. He also trusted Lovett to act as Secretary of State when he had surgery in late 1948.

Marshall and Lovett with President Truman working on the Economic Recovery Act.

Marshall called on Lovett again when he became Secretary of Defense in 1950, asking him to serve as Deputy Secretary of Defense, and fully intending for Lovett to succeed him. Marshall had agreed to stay only a year, and when Marshall left in 1951, Lovett was sworn in as the fourth Secretary of Defense.

Lovett taking the oath of office as the Secretary of Defense in 1951, with Marshall and his family looking on.

Marshall and Lovett kept up their association in the following years of Marshall’s retirement, with Lovett and his wife, Adele, visited the Marshalls at their home in Leesburg, VA, several times.

Adele Lovett, Marshall, Katherine Marshall, and Lovett at the Marshalls’ home in Leesburg.

Lovett’s dedication to Marshall did not end with Marshall’s death – Lovett served as a pall bearer at Marshall’s funeral; he served as Chairman of the Board of Trustees at the George C. Marshall Foundation and attended the dedication of the Foundation building in 1964.

Lovett (third from left) serving as a pall bearer at Marshall’s funeral in 1959.

Lovett and Dr. Forrest Pogue enjoy a chuckle at the dedication of the George C. Marshall Foundation building in 1964.

Melissa has been at GCMF since fall 2019, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.