by Molly Guptill Manning

All photos provided by the author unless otherwise noted.

The history of World War II is replete with examples of great political and military leadership, but there is one figure whose unique background and long experience made him the perfect candidate to raise an Army of civilian-soldiers and prepare them to face some of the gravest battles the world has seen. George C. Marshall’s circuitous route to becoming Army Chief of Staff in 1939 caused him to develop a unique understanding of what made troops great soldiers: morale. And when it became his responsibility to transform millions of Americans into soldiers, his unconventional focus on soldier morale helped build the U.S. Army into one of the greatest fighting forces in the world.

Marshall’s path to becoming a five-star general began at the Virginia Military Institute, which, in the 1890s, was not a gateway to a military career. In fact, in 1890, only a handful of VMI graduates served in the regular Army. Though his performance was average academically, Marshall distinguished himself in military discipline and aptitude. But Marshall was sensitive to how many struggled to adjust. Two of Marshall’s roommates ultimately dropped out, unable to bear the leaden hand of unrelenting military precision and protocols. Marshall witnessed their wilting reactions, marked by obscene language, crude manners, open resentment, and purposeful rule violations. Rather than become embittered towards these men, Marshall developed an empathy for them.

After Marshall graduated from VMI and was awarded a commission, he was sent to a remote post in the Philippines where he was the only officer and his men were forced to perform grueling tasks that prompted bitter complaints. Though Marshall maintained order and discipline, he did not ignore their gripes. He believed that if their discontent festered, he could have a mutiny on his hands. Though it was rather un-army-like, Marshall ordered supplies to boost their spirits: checkers, playing cards, books, magazines, and games. When boxes of recreational items arrived, the men were visibly moved. By recognizing their hard work and the tough jobs they performed, Marshall earned their esteem and respect. From that point forward, troops willingly performed back-breaking, dirty, menial tasks for Marshall because they knew their commanding officer valued them.

Marshall continued to experiment with morale activities for decades. Perhaps most relevant to this story, however, was Marshall’s experience in witnessing troop morale in France during the Great War. After an Army Intelligence report reported tragically low morale among foot soldiers in France, General John J. Pershing ordered an investigation on how to improve morale. Pershing was informed that what troops wanted most was the news. Unable to see beyond the range of their own foxhole, troops had no context to understand the importance of their own fighting, or whether the war was coming any closer to an end. Pershing immediately resumed publication of the Civil War’s popular newspaper, The Stars and Stripes, for distribution across France, and ordered tens of thousands of popular homefront magazines. Once information began to circulate, the Army Intelligence Branch reported a noticeable uptick in troop morale. It was perhaps this first-hand observation of the role of information in wartime that inspired Marshall’s solution to the morale problems he faced in his first years as Chief of Staff.

Marshall understood that troops needed an escape from the stress of training, and later combat. By giving them access to civilian pleasures—like movies, sports equipment, stories, and games—they would be able to relax in their off-duty hours and have a mental respite from the day’s rigors.

As war erupted in Europe in 1939, America remained deeply isolationist and politicians were reticent to approve funding for the military. This reluctance stymied Marshall’s ability to prepare the Army for possible entry into the war. It was not until the fall of France in mid-1940 and the passage of the first peacetime draft in American history, that Marshall was able to begin raising, and investing in, a modern Army. With the draft, Marshall was confronted with millions of civilians who had no background in the military, and harbored little interest in wearing a uniform and learning to fight. Many resented leaving home, losing their individuality, and following orders and instructions from sunup to sundown. In addition, the Army lacked sufficient uniforms, weaponry, and training facilities for the huge numbers of troops being drafted. Malcontent skyrocketed as civilian-soldiers were forced to pitch tents during the winter, wear leftover uniforms from World War I, and pretend broomsticks were guns during field exercises. While many commissioned officers and high-ranking personnel had no patience for the gripes, growing pains, and grievances of these civilian-soldiers, Marshall looked at this problem differently. He remembered his struggling roommates at VMI, his first assignment in the Philippines, and the Americans in France during the Great War. More military discipline was not the answer. Allowing troops to acknowledge their difficulties could breed good will, and giving them supplies to make their off-duty hours more enjoyable might ease the bitter adjustment to the military.

Based on this conviction, Marshall spearheaded the most comprehensive morale program the Army had ever had. Operating as the Special Service Division, a constellation of morale activities was organized and implemented. Among the main goals of the Special Service Division were to spread information about the war via film, radio, and publications; provide recreational equipment in the form of athletic gear, movies, games, theater productions, libraries, and other entertainment; and provide educational opportunities through supplemental coursework, correspondence courses, and setting up remote schools. With such diverse offerings, Marshall believed that every person in uniform could find something that would improve their experience. Information and education would help troops understand why they were going to war and the purpose of their training; as they embarked overseas, they would have some knowledge of the different theaters of war and what values were at stake. In terms of recreation, Marshall understood that troops needed an escape from the stress of training, and later combat. By giving them access to civilian pleasures—like movies, sports equipment, stories, and games—they would be able to relax in their off-duty hours and have a mental respite from the day’s rigors.

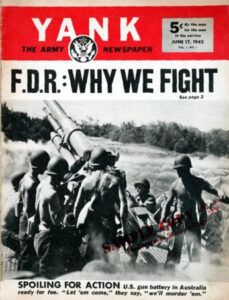

One piece of morale equipment that Marshall took a special interest in was the development of troop newspapers. He had witnessed the stark rise in morale during World War I after General Pershing resumed publication of The Stars and Stripes for troops in France. Marshall hoped newspapers could do the same for him and his Army of civilian-soldiers. However, he had some doubts about the feasibility of a troop newspaper program during World War II because the civilian press faced censorship restrictions. President Roosevelt had even signed an executive order to create the U.S. Office of Censorship to provide guidance to the media on what military information was too sensitive to print. Would soldiers be able to print anything about their military experience? To allay his concerns, Marshall approached President Roosevelt and floated his hopes for a robust troop newspaper program in the Army. Marshall was surprised to win Roosevelt’s swift and hearty approval. As it turned out, President Roosevelt had sailed aboard many naval vessels on “presidential cruises” during the 1930s, and he was familiar with the Navy’s tradition of printing shipboard newspapers for a ship’s crew. Filled with gossip, information, news, and history, these newspapers were beloved by President Roosevelt, and he preserved every copy he received. Roosevelt was such a keen supporter of Marshall’s newspaper idea that he even submitted a piece for publication for a magazine Marshall was planning to start, called Yank the Army Weekly. Even though he had created an Office of Censorship at home, it seems Roosevelt envisioned a wide degree of free expression for Yank. In his article for Yank, Roosevelt said that Yank represented freedom that America’s enemies could not fathom. “It is inconceivable to them that a soldier should be allowed to express his own thoughts, his ideas and his opinions,” Roosevelt said. “But here is the evidence that you have your own ideas, and the intelligence and humor and the freedom to express them,” he added. Roosevelt encouraged troops to write and read. By doing so, he said troops would act as “delegates of freedom” around the world.

Marshall believed that these small newspapers were especially important in maintaining morale because they allowed troops to personalize their experiences and see how their specific work mattered.

Just as Roosevelt dedicated troops to exercising their freedom of expression in Yank, Marshall wrote a piece for publication in The Stars and Stripes to announce his liberal editorial policy. Perhaps to quiet officers and generals who were horrified by the idea of low-ranking troops printing a free-wheeling Army newspaper, Marshall stated in his article that it was General Pershing’s policy during the Great War that “no official control was ever exercised over the matter which went into The Stars and Stripes”—it was to be “entirely by and for the soldier.” Following this precedent, Marshall said that he would adopt the same policy. For the duration of the war, whenever an officer disliked what was being printed (General George Patton loudly complained and wrote letters to the paper expressing his dissatisfaction with its contents), the low-ranking staff cited General Marshall’s “no official control” policy and they continued to print what they wanted.

Although Yank and The Stars and Stripes reached millions of troops each week, Marshall still felt that something more was needed to build morale and comradery among troops. During World War I, some enterprising soldiers created small newspapers for individual units to herald the unique tasks they performed—from forestry and railroad work to combat. Troops made sense of their losses, honored their dead, celebrated their victories, and made sense of how their non-combat work contributed to battlefield missions. Marshall believed that these small newspapers were especially important in maintaining morale because they allowed troops to personalize their experiences and see how their specific work mattered.

The Special Service Division had already created “kits” for its different offerings—a crate of athletic equipment for a “sports kit,” a container of film supplies and a projector for its “movie kit,” an assortment of musical instruments for its “music kit,” and folding bookshelves full of books for its “hardcover book kit.” Why not add a newspaper publishing kit to the mix? With Marshall’s goading, one was made. Soon, a chaplain or officer could request a “publishing kit” from the Special Service Division and a crate was dispatched containing typewriters, ink, paper, and a mimeograph machine for duplication. Ink and paper were replenished every few weeks, and troops were able to print newssheets for the duration of the war. Manuals and a monthly newsletter were provided by the Special Service Division to provide writing and publication guidance.

Marshall seemed to innately understand that troops would tolerate bad conditions, difficulties, and setbacks so long as they could make sense of these happenings and understand the importance of what they were doing.

Before long, over 4,600 unique newspapers were being produced by American units around the world. Many adopted colorful and humorous names that reflected their work or attitude toward the military. To provide a few examples, one hospital newspaper was called the Gauzette, a parachute division called its newspaper The Screamer, a separation center printed The Home Crier, a combat unit in Europe produced The Scars and Gripes, and an overseas aviation battalion proudly chronicled its action in Tough Sheet. Because military censorship applied to these newspapers, troops could not identify their exact location, and if they printed any information that was considered sensitive, they were prohibited from mailing them home. However, when censorship did not bar mailing, troops often tucked their unit newspaper in a letter to loved ones. Scribbled above many mastheads were requests for family members to save each newspaper so the soldier would have them when he returned home. As one soldier wrote, “Save these for me when I send them, will you mother?”

Just as Marshall had hoped and predicted, troop newspapers helped civilian-soldiers adjust to the military by acknowledging how difficult their training was, how miserable the conditions could be, and how they came through these challenges together. Marshall seemed to innately understand that troops would tolerate bad conditions, difficulties, and setbacks so long as they could make sense of these happenings and understand the importance of what they were doing. As the Pulitzer-Prize winning cartoonist Bill Mauldin said, war was full of indignities and injustices, and it was important to give troops newspapers that acknowledged these things. In Mauldin’s words, if a soldier “picks up his paper and reads a letter or sees a cartoon by some other soldier who feels the same way,” the man’s resentment is replaced with validation and his full focus could return to his job. Just as they could air-out their frustrations and anger, troops also used their newspapers to celebrate their gains and accomplishments. Marshall believed that praise for a job well done was most meaningful when “in the presence of those who had shared in the action.” Even commanding officers took to the pages of their troop newspaper to lavish praise on their men’s achievements. On the heels of the Battle of the Bulge, Major General A. R. Bolling submitted a letter for publication to the 84th Division’s newspaper, the Railsplitter, to commend the incredible advances the division had made. “You have accomplished what many thought was impossible,” he said. “Without your drive and determination, without your spirit and courage, the drive would not have been accomplished as expeditiously—the credit is yours,” Bolling added.

Marshall’s newspaper program had a long-lasting effect. Millions of soldiers returned to the United States after the war with a habit of reading newspapers and magazines to keep informed and understand the world around them. Subscriptions to domestic newspapers and magazines skyrocketed after the war, as returning veterans felt a duty to keep abreast of local and global events in order to preserve the hard-won peace they had achieved. As one soldier said in an editorial published in the final wartime issue of his unit’s newspaper: “The price of peace is eternal vigilance, [and] we must be well informed, and keep informed as to what’s going on at home and in the world…. In the time to come…. let’s pledge to do our part, to keep informed, and to keep the best country in the world out of another war.”

Molly Guptill Manning is an Associate Professor of Law at New York Law School, where she teaches Legal Practice, Civil Procedure, and Professional Responsibility. Her book The War of Words: How America’s GI Journalists Battled Censorship and Propaganda to Help Win World War II, is available from Blackstone Publishing.

Molly Guptill Manning is an Associate Professor of Law at New York Law School, where she teaches Legal Practice, Civil Procedure, and Professional Responsibility. Her book The War of Words: How America’s GI Journalists Battled Censorship and Propaganda to Help Win World War II, is available from Blackstone Publishing.