The death of two members of the Tuskegee Airmen in mid-January reminded the country of the significant contribution that African Americans made to World War II. As chief of staff of the United States Army, George C. Marshall was directly involved in the establishment of the military program for aviation at the Tuskegee Institute. Correspondence between Marshall and Frederick D. Patterson, president of the Tuskegee Institute, shows that Marshall expressed an interest in developments at the Tuskegee Institute throughout the war and offered whatever support he was able to help the program succeed.

The death of two members of the Tuskegee Airmen in mid-January reminded the country of the significant contribution that African Americans made to World War II. As chief of staff of the United States Army, George C. Marshall was directly involved in the establishment of the military program for aviation at the Tuskegee Institute. Correspondence between Marshall and Frederick D. Patterson, president of the Tuskegee Institute, shows that Marshall expressed an interest in developments at the Tuskegee Institute throughout the war and offered whatever support he was able to help the program succeed.

Shortly after the establishment of the aviation program at the Tuskegee Institute Marshall wrote to Patterson and observed that it “could probably use some vocational or manual training equipment.” Marshall included information about several federal programs to which Patterson could apply for assistance in obtaining the necessary equipment.

In a telegram dated July 22, 1941, Patterson thanked Marshall for his, “splendid message which added much to the significance of our program… when the pilot training program for the 99th Pursuit Squadron was officially inaugurated.” Although Marshall was not able to attend the ceremony, his decision to prepare a message for the occasion indicates the significance the event had for Marshall as well as his desire to encourage the Tuskegee Airmen to do their best so the program would succeed.

Despite the valuable service the Tuskegee Institute provided to the nation its requests to obtain equipment from federal agencies were repeatedly denied and promises for additional support from the Army in the form of expanded programs and resources were often unfulfilled. After receiving another message that the Army had decided not to expand training programs at the Tuskegee Institute, Marshall wrote to Patterson, “The War Department is doing its utmost, consistent with military interests, to treat all races, communities, and states fairly in the assignment and training of troops.” Marshall acted in accordance with this statement and never considered race as the basis for any of his decisions. His primary concern was defeating the Germany and Japan as quickly as possible, and he welcomed all Americans to lend their support to the war effort.

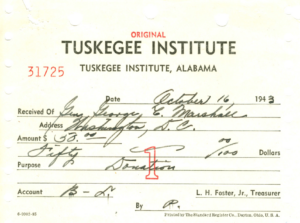

After learning that the Tuskegee Institute was experiencing a significant loss in donations, George C. Marshall contributed $50 along with his “best wishes for your success in raising the needed funds to carry on the good work of Tuskegee Institute.” In thanking Marshall for his contribution Patterson wrote, “I regard you as already one of our benefactors. I am constantly grateful for what you have done to make it possible for Tuskegee Institute to render a large measure of service to the war effort.”

After learning that the Tuskegee Institute was experiencing a significant loss in donations, George C. Marshall contributed $50 along with his “best wishes for your success in raising the needed funds to carry on the good work of Tuskegee Institute.” In thanking Marshall for his contribution Patterson wrote, “I regard you as already one of our benefactors. I am constantly grateful for what you have done to make it possible for Tuskegee Institute to render a large measure of service to the war effort.”

The Marshall-Patterson correspondence reveals that Marshall’s contributions to the Tuskegee Institute extend far beyond being the head of the Army when the program was initiated. Marshall’s support of the Tuskegee Institute in the form of training equipment, words of encouragement, and personal contributions, reveals his deep commitment to the program and his desire for its success.

To view additional resources about the Tuskegee Institute found in the research library and archives, visit the library’s newly created subject guide.