Lt. Col. George Marshall had just taken a position teaching at Army War College in Washington, D.C., when his wife, Lily, passed away unexpectedly. Marshall was devastated and unhappy. “At a War College desk I thought I would explode,” he wrote to Leavenworth friend Stephen Fuqua.

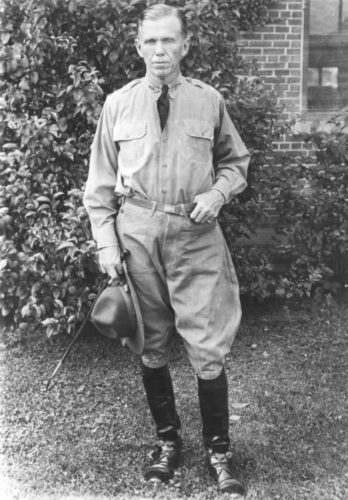

Lt. Col. George Marshall

Realizing that Marshall’s despondency was in part connected to Lily’s memory in their home and amongst friends in D.C., he was given the option of going to Fort Benning, Georgia, to be assistant commandant at the Infantry School, a position he had long wanted.

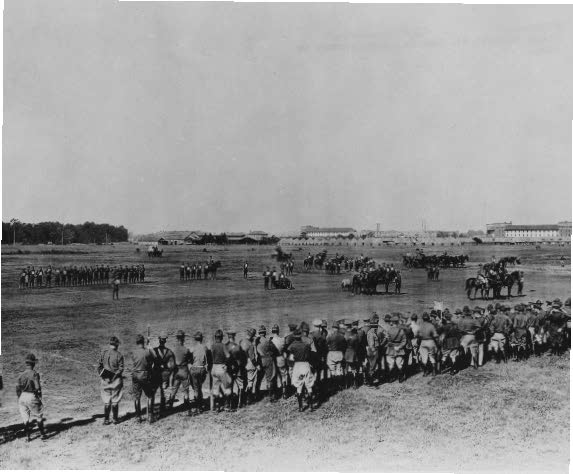

Fort Benning front gate, 1927

About a month after Lily’s death, he wrote to Lily’s “Aunt Lottie,” Mrs. Thomas B. Coles:

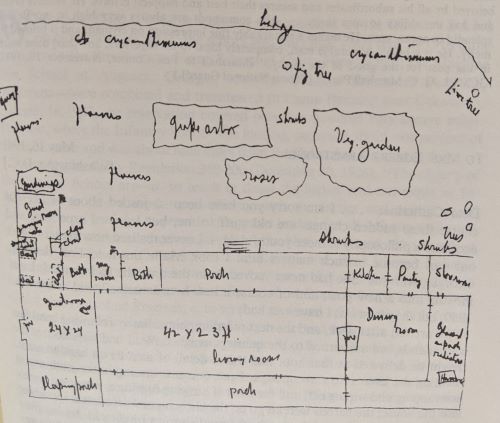

“There has been a violent change in my affairs. Yesterday the Chief of Staff appointed me assistant commandant of the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. The house I will occupy was a farm house before the government took over the place in 1918. So you see I will lead a country life, which is what I need.”

Sketch of the Fort Benning house by Marshall in his letter to Aunt Lottie

Fort Benning officer quarters

He packed his house full of treasures Lily had purchased in China, and with his sister, Marie, headed South. On the way, they visited with Aunts Lottie and Charlotte in Virginia.

Marshall visiting Aunt Lottie on his way from Washington, D.C., to Fort Benning.

The middle of November, he wrote again to Aunt Lottie:

“Our freight arrived at the house, and ever since we have slaved from early morn until well after dark. My poor sister has worked so hard she complains bitterly of ‘misery’ in her feet. You and Charlotte were very sweet … and I am grateful accordingly. I was very glad to be with you on my way to new scenes and surroundings under such changed conditions. It served to me as a warm reassurance that my ties over so many years were not to be entirely disrupted.”

Marshall at Fort Benning

At Infantry School, Marshall knew that old tactical problems would not work for the modern, and very mobile Army. Students needed to analyze new tactical problems based on real issues.

As assistant commandant, Marshall was in charge of the Academic Department, and was able to form courses and teaching as he wanted.

New barracks, and maneuver field in the background, Fort Benning, 1928

According to his biographer, Dr. Forrest Pogue, Marshall had “strong and revolutionary ideas, many of which had been developing in his mind for some years,” and now he was able to apply these ideas to the training of officers.

It was, Marshall admitted, “an almost complete revamping of the instruction and technique,” but he had to proceed cautiously, “quietly and gradually, because I felt so much opposition would be met on the outside that I would be thwarted in my purpose.”

Infantry School instructors

Marshall shrank the class size at Infantry School, as he felt large lecture halls were not conducive to learning. He also declared that lectures were not to be read; he though teaching was more effective when an instructor talked more informally.

Instructors for the Tactics and Weapons Section at the Infantry School, including Joseph Stilwell, Edwin Harding, and Omar Bradley.

He also chose and treated instructors in a very specific manner. He wanted to:

- Recruit a superior staff

- Give them their assignments

- Leave them alone.

- If they hesitate, help

- If they fail, relieve them

Marshall wanted students to think on their feet. Once he rode with students over a 17-mile course, and at the end, asked the students to draw a map of the country they had traversed.

Training at Fort Benning

Marshall had good reason for wanting this ability, as pointed out in a lecture:

“Picture the opening campaign of a war. It is a cloud of uncertainties, … congestion on the roads, strange terrain, lack of ammunition and supplies at the right place at the right moment, failures of communications, terrific tests of endurance, and misunderstandings in direct proportion to the inexperience of the officers. Add to this a minimum of preliminary information of the enemy … poor maps, and a speed of movement or in alteration of the situation, resulting from fast flying planes, fast moving tanks, armored cars, and motor transportation in general. There you have warfare of movement such as swept over Belgium or Northern France in 1914. That, gentleman, is what you are supposed to be preparing for.”

In the field at Fort Benning

In his first year at Fort Benning, his sister Marie visited several times. She was “disturbed by the fact that her brother kept the house filled with photographs of Lily so that in moving from room to room he was constantly reminded of his loss,” according to Pogue.

Marshall, Mrs. Nettie Hoge, Katherine, Gen. William Hoge at Fort Benning

This began to change in the spring of 1929. He met Katherine Brown, a widow, at a friend’s house in Columbus. They hit it off, and Marshall invited her to a reception on Post the next evening. They wrote to each other over the summer.

Marshall and Katherine horseback riding at Fort Benning

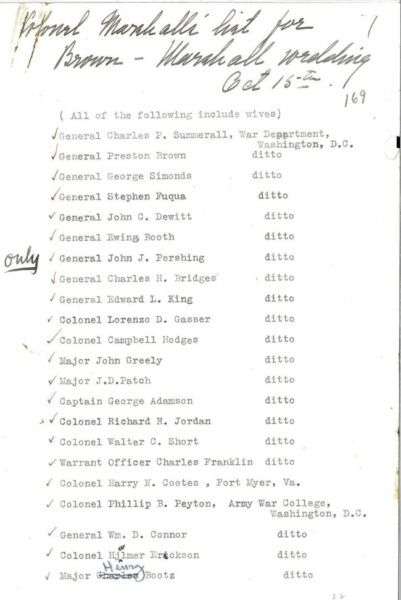

He hoped she would visit Columbus again, and she did in the spring of 1930. Marshall cleared his calendar so they could spend every evening together. Katherine would not consent to become engaged until her children had a chance to spend some time with Marshall. He spent five weeks with the family and friends at Fire Island, New York, that summer, and when he returned to Fort Benning, he wrote Gen. Pershing, “we are to be married in Baltimore the afternoon of Oct. 15th. I would count it a great honor if you would stand up with me. The wedding is to be quiet with only family and very intimate friends.”

List of friends and associates to get wedding announcements

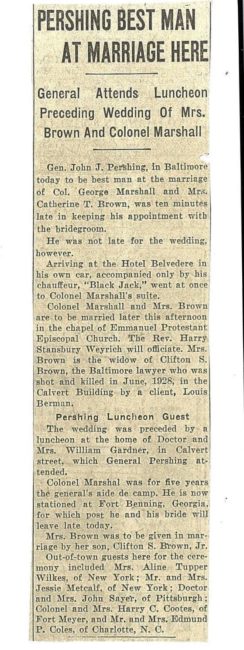

Other attendees at the wedding included Katherine’s sister Allene, Marshall’s sister, Marie, and Lily’s brother, Edmund. After the ceremony, he wrote and thanked Pershing for coming, saying, “We were both sorry that so much publicity was attached to your presence, as it resulted in considerable harassment of you by the press.”

Newspaper article on the Marshall-Brown wedding

Marshall told Pershing of Katherine’s introduction to the Army life: “Mrs. Marshall is having her first touch of the Army. The business began the night of her arrival – shaking hands on the Commandant’s lawn with about 1,000 people at an al fresco reception and dance.”

Katherine had her own take on that reception. The Marshalls had left the church in Baltimore, and boarded a train headed straight back to Fort Benning as school had already begun. They went from the train station in Columbus to the reception on Post. In the receiving line, Marshall would whisper to Katherine details the person next in line, including wedding gifts they had given. Katherine would dutifully make a specific verbal thank you. After shaking so many hands and being completely exhausted, when Marshall told her the next woman in line had just had triplets, without thinking, Katherine said, “thank you for the triplets.”

Katherine Marshall in the 1930s

Marshall spent two more years at the Infantry School, and by the end of his five-year tenure, his efforts had changed the way the Army trained officers, and in a few short years, this new training would pay big dividends as he had 150 future generals of World War II amongst the students, and another 50 from the instructors.

Photos from the George C. Marshall Foundation Collection; quotes from correspondence in the George C. Marshall Papers.

Melissa has been at GCMF since last fall, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @life_melissas.