Katherine Tupper Brown Marshall, George Marshall’s second wife, was born in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, on October 8, 1882. She earned an “eclectic degree” from Hollins College in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1902. “I crawled through Hollins,” she later said. “I didn’t care about anything but going to the theatre.”

Katherine as Rosalind in As You Like It with Sir Frank Benson’s Shakespearean Company.

She continued her studies at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City for two years. “I did not care about anything else in the world – a stage-struck person,” she recalled later. Her father said that she could go to London in 1904 to study theatre, but to study acting and not pursue it on stage. Katherine defied her father, joined an English Shakespearean company and took the stage name of Katherine Boyce. She became ill in Scotland in 1905 and returned to the United States. After a year’s rest, she tried acting again but had to quit after three months when she the same illness returned.

Katherine married Clifton Brown, a Baltimore attorney, in 1911 and became a wife and mother. Recalling her adjustment to domestic life, she said, “It was hard to know whether I had gone from the sublime to the ridiculous or from the ridiculous to the sublime.” She said in 1939 that she never regretted giving up her career for a family. Clifton was murdered by a disgruntled client in 1928, leaving her with three children: Molly (16), Clifton (14) and Allen (12).

Katherine Brown with her children Allen, Molly, and Clifton in 1922.

While visiting a friend in Columbus, Georgia, in 1929, Katherine met Lieutenant Colonel George Marshall, who was head of the Infantry School at nearby Fort Benning. They were married in 1930, and General John J. Pershing was Marshall’s best man. After two years at Fort Benning, she wrote, “I was a fair Army wife. At least I had learned many things, among them to be on time, to listen rather than to express opinions, that lieutenants do not dance with colonels’ wives for pleasure, that acquiring a good seat in the saddle takes endurance beyond the power of man to express.”

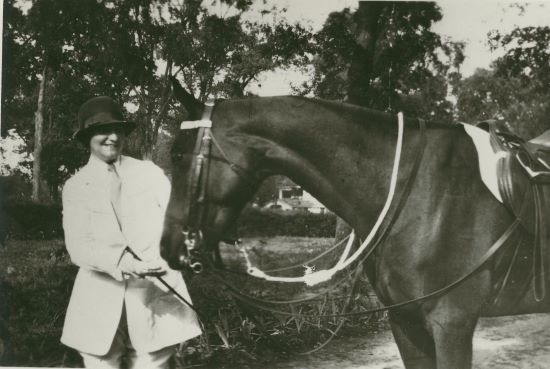

Katherine Marshall with her riding horse at Fort Benning, GA.

Katherine was by Marshall’s side as he rose through the ranks to become Army chief of staff, and they were never separated for more than a few days at a time. Marshall sometimes worried that she was taking on too many responsibilities – to the detriment of her health. He told her son Allen in 1942, “I cannot persuade her to lighten her own burdens: telephone, mail and committees. She resents my ideas of procedure and suffers accordingly. Her mail has become voluminous, telephone calls are more numerous than ever, and demands on her to attend meetings a daily matter. … It is idle to expect her to change her ways at this time. We just have to make the best of it.”

Katherine in the mid-1940s.

Marshall’s retirement from the Army in 1945 was supposed to give him freedom from obligations, but he couldn’t say “no” when President Harry Truman asked him to be special envoy to China in 1946, secretary of state in 1947-49, president of the American Red Cross in 1949-50 and secretary of defense in 1950-51. He told Sir Hastings Ismay of Great Britain in 1950 that Katherine was “game” about his appointment as secretary of defense but that she was “profoundly depressed” when the press reported that she had been “delighted.”

George, using a cane, and Katherine in China in 1946.

Katherine complained in December 1945 about Truman’s decision to send Marshall to China, which she called a “bitter blow.” She said that “The president should never have asked this of him and in such a way that he could not refuse. I get a sickly smile” “when people say how the country loves and admires my husband.” She expressed bitterness “that he should be assigned, just at the time of retirement, to be a messenger boy between the Generalissimo [Chiang Kai-shek] and the Communists.” Katherine accompanied Marshall to China but was unhappy about his hard work, telling his secretary, “Gen. M. is working day and night to bring some kind of accord…He looks so thin to me and is very tired.”

Katherine in North Carolina about 1971.

After Marshall’s death in 1959, Katherine moved to a residential hotel in the North Carolina mountains, enjoyed friends and traveled. She was a guest of honor at the famous Nobel and Pulitzer Prize dinner given by President John Kennedy in 1962. Katherine had a severe stroke in 1976 and moved to the Loudoun Hospital in Leesburg, Virginia, where she repeatedly complained to nurses that “They kept taking my George away from me.” An unidentified person sent her flowers regularly, and she told the staff that they were from her husband.

Katherine Marshall died December 19, 1978, at 96 years of age. She is buried at Arlington National Cemetery next to Marshall, his first wife, and his first wife’s mother.

Tom Bowers is the former docent director at George Marshall’s Dodona Manor in Leesburg, Virginia. He was professor and dean of the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1971 to 2006.