George Marshall refused to write his memoirs, but he was persuaded to be interviewed and to have his biography and papers published. He rejected any role in the selection of an author and stipulated that all proceeds should go to the George C. Marshall Foundation, which selected Dr. Forrest Pogue to interview Marshall and write what became the authoritative biography, published in four volumes from 1963 to 1987.

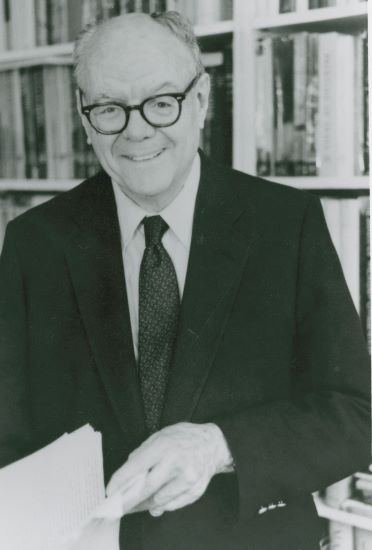

Dr. Forrest Pogue (University of North Texas photo)

Pogue had an undergraduate degree from Murray State University in Kentucky, a master’s degree from the University of Kentucky and a Ph.D. from Clark University. He was on the faculty at Murray State when he was drafted by the Army in 1942. He later said that he had been pulled from a foxhole-digging detail when his commanding officer received an order to “find a soldier with a Ph.D. in history,” and he was reassigned to a special Army historical unit. After Pogue interviewed wounded soldiers after the Normandy invasion, he accompanied Allied forces across France and into Germany.

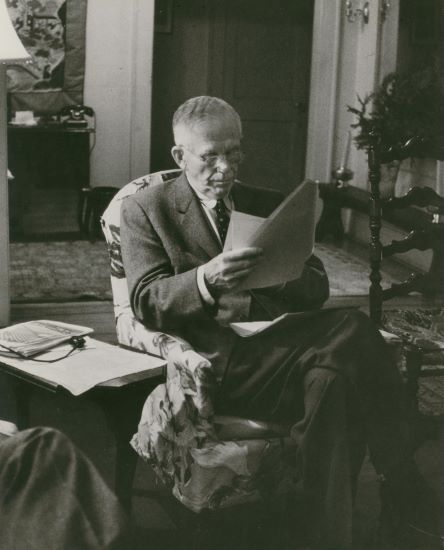

Pogue during World War II

He had never met Marshall until he began the interviews at Dodona Manor, Marshall’s home in Leesburg, Virginia, in September 1956. Pogue told him that he had been at the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo in 1953, and that broke the ice and led to easy conversations. Marshall arranged to have Pogue use Marshall’s office in the Pentagon when he needed to be there for research. When Pogue went to Leesburg for the first of the interviews, Marshall insisted that they first listen to a World Series game (New York Yankees vs. the Brooklyn Dodgers, Marshall’s favorite team). Pogue said that listening to the game made the interview easier.

Pogue (left) and Marshall during interviews at the Marshall home in Pinehurst, NC. The mic to the tape recorder is on the table between them.

Marshall was given a tape recorder to be used to record his answers to questions that Pogue wrote for him. Sgt. William Heffner, Marshall’s orderly, operated the tape recorder while Marshall and Pogue talked. Occasionally, Marshall answered the questions without Pogue being present. In his first recording, Marshall said, “I have no idea how to approach this, because there is so much that I might say—and it is much too much—and just what angle I should take is a matter still to be determined, but I thought that the best way to do was for me to make a start and then you could advise me as to what is needed.” He later told Pogue, “I do not ask you to write one way or another. You will succeed if you remember to deal with our stories with the understanding of what we knew at the time, what we had to do with, and what we attempted to do in a limited time.”

Marshall refused to answer Pogue’s request to evaluate American and foreign leaders that he had encountered. He told Pogue that he did not want readers looking to find “insults” about other people. Pogue, however, said that he was able to discern Marshall’s attitudes through his tone of voice.

Pogue recalled times when Marshall said, “Turn that damn thing off and I’ll let you in on something.” Those “somethings” were usually tidbits that Marshall thought should not be published. On one tape, Marshall is heard to give a sudden warning, “Johnny, don’t touch that mike!” followed by a directive for Johnny (apparently a neighbor boy) to go to the kitchen. To Katherine, Marshall said, “Katherine, take this cannibal and feed him!”

The last taped interview was on April 11, 1957, in Pinehurst. Marshall promised Pogue he would continue in May when he returned to Leesburg, but his health deteriorated, and he did no more interviews.

The interviews, with transcripts, are available at https://www.marshallfoundation.org/library/collection/george-c-marshall-interviews-reminiscences/#!/collection=341. Nothing compares to hearing Marshall tell his stories in his own voice.

A transcript of the interviews is published in George C. Marshall: Interviews and Reminiscences, edited by Larry I. Bland and published in 1996. Pogue ended his introduction to that volume by saying that he had “profited from glimpses into the way he [Marshall] thought and made decisions, and that these talks with him gave me a closer understanding of Marshall the human being than I could otherwise have gained.”

Tom Bowers is the former docent director at George Marshall’s Dodona Manor in Leesburg, Virginia. He was professor and dean of the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1971 to 2006.