While a cadet at the Virginia Military Institute, George Marshall studied military history and tactics, and was doubtless familiar with Napoleon Bonaparte’s ill-fated attack on Russia that ended with French soldiers freezing in the Russian winter. As a young officer in World War I, Capt. Marshall first met Gen. Pershing when he disputed Pershing’s scathing assessment of his unit, which was short on uniforms and equipment.

When Marshall became Chief of Staff of the Army in 1939, making sure soldiers had what they needed to train, and then to fight, was extremely important to him. He explained his view in a speech to the American Legion in 1943: “My consideration is for the American solider, to see that he has every available means with which to make successful war, that he is not limited in ammunition, that he is not limited in equipment.”

When he learned early on that the Army was enduring clothing shortages, he said, simply, “I am interested in the soldier having his pants.”

As the Quartermaster Corps developed new and better clothing items, Marshall was known to have received officers into his office while he was sitting on the floor with members of the Quartermaster Corps, examining new items, sometimes even ripping open seams in a proposed overcoat to check it for comfort and practicality.

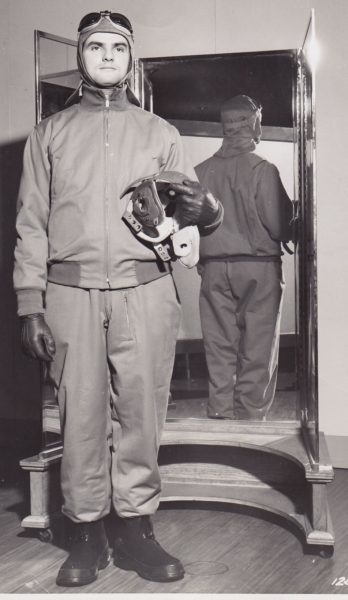

New armored winter uniform.

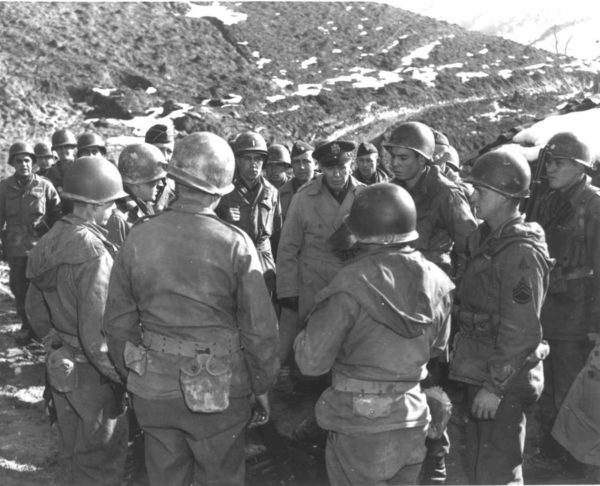

Marshall took this attitude for the soldier with him wherever he visited. He told Dr. Forrest Pogue in a 1957 interview, “The big thing I learned in World War II was the urgent necessity of frequent visits … I was abreast of what was going on all over the place. I could sense their reactions and I could see how they felt urgently about this or that, which we at headquarters did not really feel so much, but I would come to an understand in those ways and I could correct things almost instantly.”

Marshall’s orderly, Sgt. James Powder, added to this statement when he told Pogue in a 1959 interview, “He told me that whenever he went to a place, he tried to find out what it was they were lacking, and that he’d get it.”

Gen. Marshall visiting with troops in Italy, February 1944.

Powder illustrated Marshall’s concern for the solider when items requested were not supplied when the 1st Division was sent from New York to Fort Benning, GA. When Marshall visited them, Powder was approached by one of the unit’s sergeants, who reported that “the men all came down here just with one or two blankets. It’s damn cold down here.” Powder responded that he’d see what he could do. On the way back to Washington, D.C., Powder told Marshall that the division was shipped to Georgia without the supplies they needed. “They’ve only got two blankets. One of the first sergeants asked me if it would be possible for him to get some quilts.” Marshall answered, “We’ll take care of that as soon as we get to Washington.”

Uniforms being made for the Quartermaster Corps.

Some time later, Marshall and Powder visited Fort Benning again. The first sergeant came to Powder again and said, “You’re a helluva fine friend.” When Powder asked why, he said, “We’re still waiting for them quilts.” When Powder told him they had been ordered, the sergeant retorted, “Well, it is a helluva long order.”

When Powder reported to Marshall that the order had not been filled, Marshal was furious; the first time Powder had seen him truly angry. Marshall called supply personnel into his office and demanded to know why. The personnel said that the proper requisition forms were not filled out. Marshall exploded, “Get these blankets and stoves and every other damn thing that’s needed out tonight, not tomorrow morning, and not two weeks from now. I don’t care what regulations are upset or anything of that character. We are going to take care of the troops first, last, and all the time.”

Soldiers from the 10th Infantry in full winter uniforms.

Marshall continued to insist to supply staff that uniforms and materiel be moved from warehouses to soldiers in the field, so the soldier could have his pants.

Melissa has been at GCMF since last fall, and previously was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Keep up with her @life_melissas.