Cooperation, admiration, and some disagreements

George Marshall and Sir Winston Churchill had a long, but not always peaceful, association. They first met in 1919, when Capt. Marshall was Aide-de-Camp to Gen. John Pershing. Pershing and Marshall were in London, and Churchill, then serving as Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air in the British War Office, came to review U.S. troops at Hyde Park. Marshall was his assistant during the visit, and photos show them laughing and talking together.

Maj. George Marshall and Secretary Sir Winston Churchill, Hyde Park, London England, 1919

They worked together again when Churchill, then Prime Minister, visited Washington, D.C., with British military personnel who would become part of the Combined Chiefs in December 1941. The Marshalls entertained the military personnel for Christmas, but Churchill spent the holiday at the White House. American and British military leaders, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill met for the first wartime conference during the holidays, which they called “Arcadia.”

James Ernst sketch of the Arcadia Conference

During the conference, Marshall pushed hard for the idea that all British and American forces (of all services) should have a single commander in each theater of war. Churchill didn’t like this “unity of command.” He said that an army officer didn’t know enough about handling ships, to which Marshall responded, “What the devil does a naval officer know about handling a tank?”

This conference prompted the organization of the U.S. Joint Chiefs soon after, as the United States didn’t have a cooperative arm of combined military leaders to equal the British, and the President wanted the U.S. military organization to be equal to the British.

During World War II, Marshall and Churchill mainly saw each other at conferences, but there were frequently meetings before and after the general plenary sessions and between conferences. and Churchill visited training sites in the United States, and Marshall visited training sites in Germany.

Late one night in June 1942, Churchill was pushing Marshall and the President for the United States to send a large number of soldiers to the Middle East. Marshall disagreed, saying it was “an overthrow of everything they had been planning for.” Marshall then walked out of the meeting, saying he wasn’t willing to talk about the topic “at that time of night,” leaving a likely astonished prime minister and president.

Later in the war, Churchill kept Marshall up late again, pleading for a delay in the cross-Channel invasion. At a meeting the next day, Churchill argued for an operation to taking the island of Rhodes off the coast of Turkey, saying “his Majesty’s Government can’t have troops standing idle. Muskets must flame.” Marshall, in his irritation, snapped at Churchill, “not one American soldier is going to die on [that] goddamned beach.”

Aside from the conferences, Marshall and Churchill visited training units in both Great Britain and the United States as troops prepared for war.

Marshall, Field Marshal Sir John Dill, Churchill, and Secretary of War Henry Stimson viewing airborne training at Fort Bragg, NC.

Marshall (second from right) and Churchill (far right) viewing training at Salisbury Plain, England

When Marshall became Secretary of State in 1947, he wouldn’t be working with Churchill, whose party was not in power at the time. Still Churchill sent him a message of confidence: “It gives me great confidence in these days of anxiety to know that you are at the helm of the most powerful of nations, and to feel myself in such complete accord with what you say and do.”

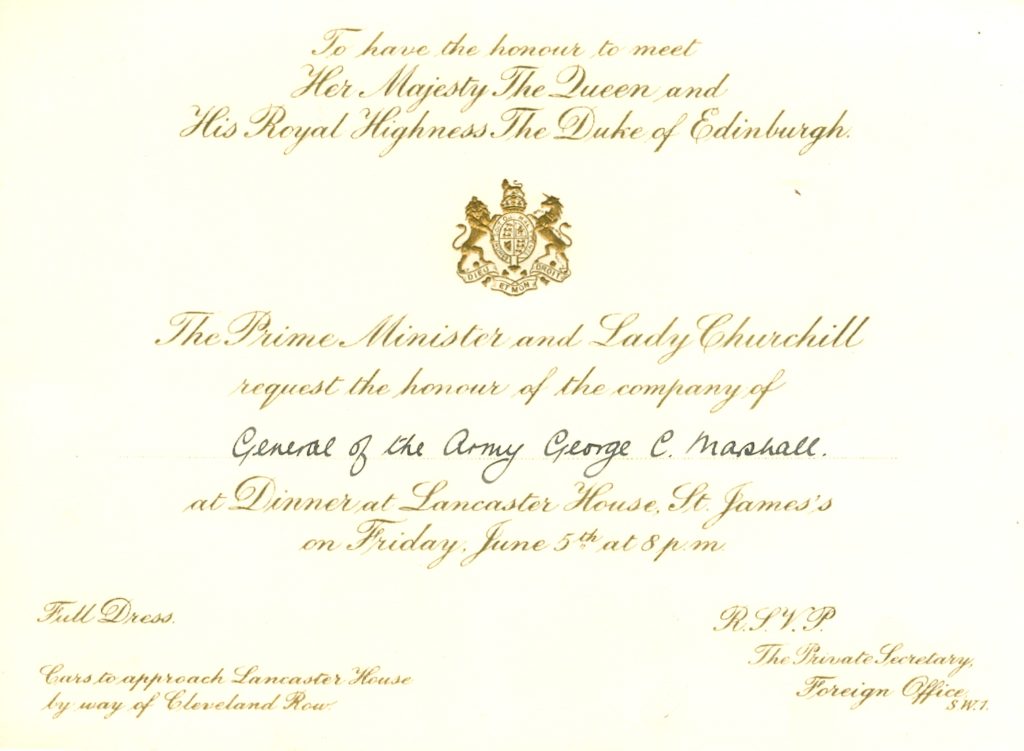

Churchill was again prime minister when Marshall was asked to be the official government representative at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. Marshall and Katherine were invited to a dinner hosted by Churchill, and there’s a fun-spirited photo from the trip showing Katherine shaking her finger at Churchill.

Dinner invitation for the Marshalls during coronation week

A bit of fun after dinner

At the coronation ceremony, Churchill stepped out of the official processional to shake hands with Marshall. Writing to former President Harry Truman, Marshall recounted, “Churchill dignified me in the Abbey by turning out of the procession to shake hands with me after he had reached the dais.”

The final meeting between Marshall and Churchill was emotional, at least for the former prime minister. Accompanied by Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Churchill visited Marshall at Walter Reed Hospital in 1959. Marshall had been greatly affected by a series of strokes and didn’t know either man. Churchill cried to see Marshall lying in the hospital.

Winston Churchill called Marshall “the noblest Roman of them all,” and although there was never a particular friendship between the two leaders, there was respect, and maybe admiration.

Quotes in this blog courtesy of Mark Stoler, author of George C. Marshall, Soldier-Statesman of the American Century.

Before becoming director of library and archives at the George C. Marshall Foundation, Melissa was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with three large rescue dogs. Melissa is known as the happiest librarian in the world! Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.