In a Sunday, May 7, 1944 letter to his mother Katherine Marshall, Allen Brown, serving as a tank commander near Anzio, Italy, wrote, “Wish the ‘second front’ would open up soon … If we don’t … I’m afraid it will mean another year overseas for all of us. A lot of things could happen, but the prospect of another year away from Madge and Tupper is certainly not a pleasant one. Have just finished the last of your box and it was wonderful! All my love, mom. Allen”

Allen Brown

Tuesday, May 30 was Memorial Day.

That morning, Katherine wrote to Allen’s wife, Madge: “In the night I wake up praying – that all will be well with my boy. I am sorry you haven’t been able to get away but come when you can. Much love, Mother.”

Gen. George Marshall went to work that morning, and his driver was headed down to the cafeteria for coffee when Marshall came back out and asked to be driven home.

He sent the following telegram to Madge:

“I have just received a message from General Clark commanding Fifth Army that Allen was killed in his tank by a German sniper at ten AM May 29th near Campoleone. General Clark has sent for Clifton. Katherine is leaving here by plane at ten o’clock for New York and will go direct to your apartment. This is a distressing message to send and you have my deepest sympathy.”

Katherine recounted that a “blessed numbness comes to one in a time like this. I could not comprehend George’s words. I had only one thought – that I must get to Madge, Allen’s wife. I do not recall anything of my flight to New York. I kept repeating Allen is dead, Allen is dead — but no realization of what this meant.”

Madge was not at home to receive the telegram; although it was Memorial Day, it was not a holiday at Life magazine, so Madge was at work. She got a phone message that Katherine was in New York to visit, but Madge was not concerned as Katherine had made a point of seeing Madge and Tupper whenever traveling brought her to New York.

It wasn’t until Madge walked into her apartment building and saw Katherine and several aides from the War Department did she realize something was very wrong. Madge reported, “Going up in the elevator she [Katherine] told me that Allen had been killed. That’s how I learned.”

On May 31, Clifton, Katherine’s older son, wrote: “Dear Mom and Madge: At one o’clock in the morning yesterday, Tuesday, I received a telephone call … to be at 5th Army headquarters at 8:30 a.m. I was afraid something had happened to Allen. Gen. Clark’s aide Phil Draper was there to meet me. He confirmed my worst fears.

“I got a jeep and proceeded to the cemetery. Maj. Langford, the III Division chaplain, happened to be at the cemetery. Phil, Maj. Langford, and I took Allen’s flag-covered remains to the grave and there Maj. Langford said a few prayers and we buried him. It was a beautiful day and appropriately ‘Memorial Day.’”

Life did not stop for the Marshall family. As a member of the Junior Officers Club, Inc., committee, Katherine was in the midst of negotiations for a government-owned building for single junior officers to have social space. Madge was on her way to Wisconsin to work on a Life magazine story a few days later.

Gen. Marshall was deep in the last planning stages for the invasion of Europe, and left for England June 7, D-Day+1. Following his fact-finding trip to Normandy, Marshall visited Italy via this observation plane that flew over the area where Allen had been killed. Marshall was able to leave “his heavyhearted tribute to Allen” at the temporary Anzio Cemetery, where he got to spend 30 minutes alone at Allen’s grave.

Gen. George Marshall flying to visit Allen’s grave at Anzio.

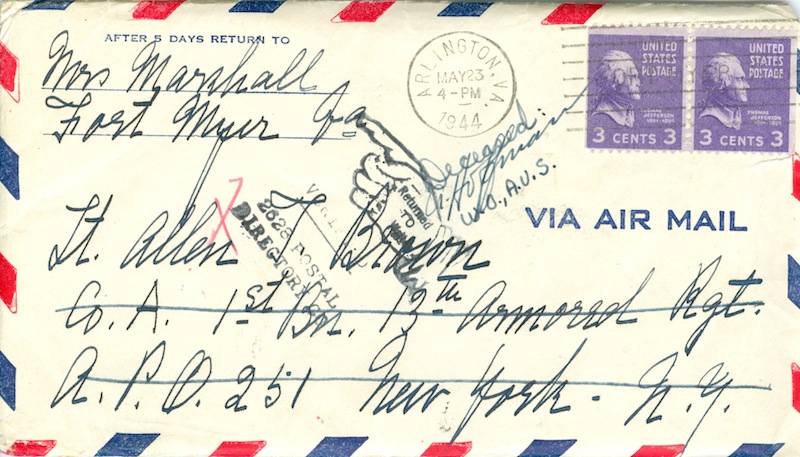

While Gen. Marshall was gone for about two weeks that June, Katherine received the following letter in the mail:

Katherine’s letter to Allen, returned, marked “deceased.”

Clifton’s letter ended “I know what a terrible shock this is to both of you as it has been to me and I only wish I could be with both of you.” It was wartime; the family couldn’t be together, so Clifton reminded his mother and Madge to “be as brave as he was. That is the way he would want it.”

Before becoming director of library and archives at the George C. Marshall Foundation, Melissa was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County with two large rescue dogs. Melissa is known as the happiest librarian in the world! Keep up with her @MelissasLibrary.