Serving in the Philippines Part 2: Other Duties as Assigned

While Marshall must have been glad to be on land after over a month of traveling, Mindoro was not an island paradise, but “was in fact a forbidding place, an island of about four thousand square miles of mountains and jungle. The towns, such as they were, spotted the coastal perimeter” and “the jungles … still sheltered armed bands of ladrones, outlaws, some of whom were former Insurrectos” (Pogue, 1963, p. 72).

Calapan was not an exciting place to serve. A little drill, housekeeping, occasional guard duty, by mid-morning Marshall had run out of useful things to do. This boredom affected the entire garrison; Marshall said they were “about the wildest crowd I’ve ever seen before or since” (Pogue, 1963, p. 74).

Marshall as a young lieutenant with the 30th Infantry, 1902 Philippine Islands.

Even though Marshall’s inter-island boat dropped anchor for cholera clearance, “Marshall had hardly had time to get acquainted when the cholera epidemic struck the region, necessitating the most rigorous enforcement of discipline on the soldiers in order to prevent their infection” (Marshall, 1981, p. 23).

The quarantine might sound familiar to us now: “Men in Calapan were confined to barracks; everything they ate or drank was boiled; hands had to be scrubbed, mess kits scoured and thoroughly rinsed. ‘A very little skimping could cost you your life’” (Pogue, 1963, p. 74). The only doctor was Marshall’s roommate, and in addition to serving as officer of the day, he would go with the doctor to work in the cholera isolation camp nearby.

The strict quarantine was effective; no soldiers died in the epidemic. When the restrictions were lifted just before Independence Day, Lt. Marshall was given the responsibility of planning the celebrations for July 4. No soldiers signed up for the games and activities. Most expected this very-junior lieutenant to be at a loss, but Marshall had an ace – prize money! When only two men entered the first race, he divided money meant for the top four finishers between the two. “As an immediate result I had a wealth of competitors for the following events and I recall that we inserted a bare-back pony race—and they were wild little captured ponies. One bolted into a native thatch house, wrecking it and dropping the girls hanging out the windows of the second story to the ground amidst much excitement and the first laughter I heard in Calapan” (Marshall, 1981, p. 24).

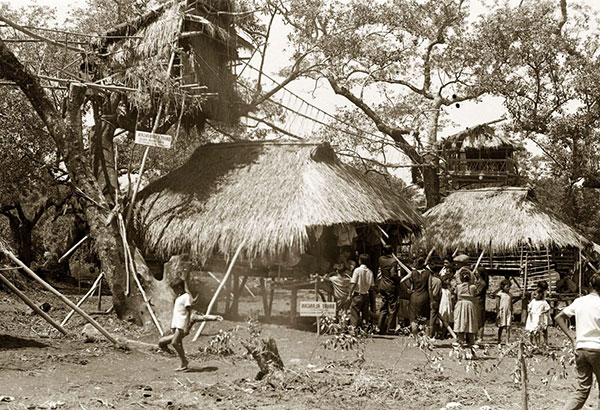

Bamboo housing, Mindoro, c1950 but not changed since Marshall’s time.

Marshall had yet another job when he was transferred to Mangarin, on the southern end of Mindoro. Within a fortnight, Marshall (at 22) was not only in charge of the company, but the entire post, and was civil governor for that side of the island. In fact, he was the only officer in the area; the only company he had was a brother from the nearby convent. Marshall didn’t speak much Spanish, and the brother didn’t speak much English!

On one patrol on Mangarin, the men “had to cross a stream, narrow but deep for fording. The lieutenant was in the lead and all the men in the water when there was a’ splash and someone yelled, ‘Crocodiles!’ In panic the men shot forward, knocked Marshall over and trod him into the mud in their haste to reach the shore. He picked himself up and waded up the bank. Standing before his men, wet and bedraggled, he realized the need promptly to reassert control. He decided very quickly that ‘it wasn’t a time for cussing around.’ Instead he formally fell them in, gave them right shoulder arms, and faced them toward the river they had just crossed. He gave the order to march. Down they went, single file, into the river, Marshall at their head, and across it and up the other side. Then the lieutenant, as though he were on the drill field, shouted, ‘To the rear-march!’ Again they crossed the crocodile river” (Pogue, 1963, p. 78).

In January 1903, Marshall was transferred to Manila, where he lived a pleasant garrison life outside the city. It is here that he learned to ride a horse, an activity that he enjoyed the rest of his life. Marshall held several jobs while in Manila. He worked in finance; he spent time in a small boat, putting up signs on islands that the military was using. It wasn’t very exciting, but Marshall reckoned that “there isn’t anything much lower than a second lieutenant and I was about the junior second lieutenant in the Army at that time’’ (Pogue, 1963, p. 80).

The last job Marshall had in the Philippines was guarding military prisoners on Malahi Island. Marshall found the duty distasteful, as the prisoners were the “‘scum’ of the Army, murderers, deserters, and the like” (Pogue, 1963, p. 82).

In November, the 30th Infantry boarded the Army Transport Sherman, and headed home, with stops in Nagasaki, Japan, and Honolulu, later important cities to Marshall, but then “for the homecoming lieutenant they were just waystops where it was possible to shop for souvenirs to take back to Lily” (Pogue, 1963, p. 83).

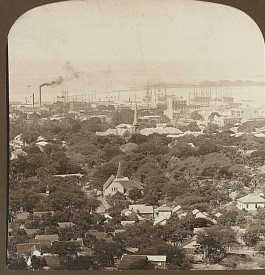

Honolulu, 1903

(1906) Honolulu and harbor, Hawaiian Islands. Hawaii Honolulu, 1906. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018647393/.

Fansler, L.D., & Postma, A. (Eds.). (2017). Bamboo Whispers: The Poetry of the Mangyan. Calapan City, Oriental Mindoro, Philippines: Bookmark.

Marshall, G.C., Bland, L. (Ed.), & Stevens, S. (Ed.). (1981). The Papers of George Catlett Marshall: “The Soldierly Spirit,” December 1880 – June 1939 (Volume 1). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins.

Pogue, F., & Harrison, G. (1963). George C. Marshall, Vol. 1: Education of a General, 1880-1939. New York: Viking.